Exactly 100 years after the pioneering exhibition Neue Sachlichkeit (1925), this autumn Museum MORE will presentnearly 80 neorealist highlights from 20 countries. This international exhibition is anything but a reprise; it offers a fresh perspective on European realism in the interwar years. In collaboration with Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz – Museum Gunzenhauser in Germany,

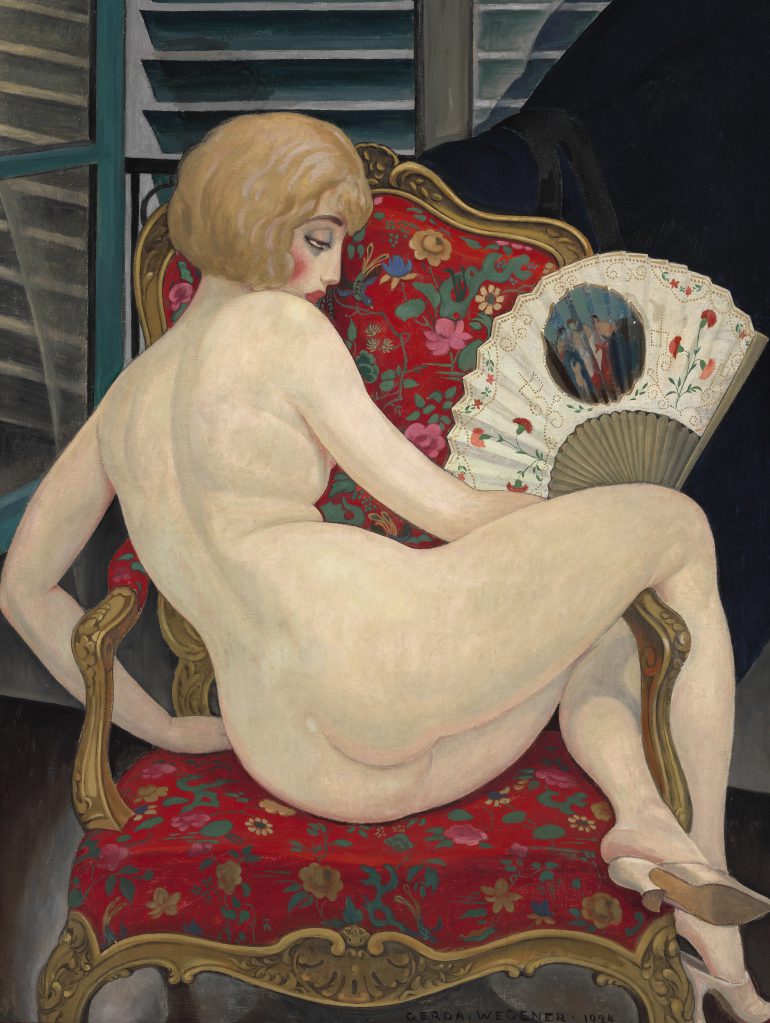

MORE will unite leading figures and rediscovered voices in the first exhibition of this scale ever held in the Netherlands. Featuring artists from Finland to Spain and from Hungary to England, among them Otto Dix, George Grosz, Meredith Frampton, Aleksandra Beļcova, Lotte Laserstein, Ángeles Santos Torroella and Gerda Wegener. Discover the rich spectrum of Realist portraits, cityscapes and still lifes – painting between silence and storm.

A new Realism in a turbulent world

For many years, realism in the arts was considered old-fashioned, classical, or even reactionary. Yet the period between 1919 and 1939 tells a different story. Out of the turbulent interwar years, an innovative art emerged across Europe that radically broke with earlier (figurative) movements.

Neorealists did not hark back to a nostalgic past, but sought instead to capture the here and now of their own time as clearly and faithfully as possible. Some artists also felt that the abstract visual language of the 1910s was unable toconvey the horrors of World War I, the unsettling socio-political developments, a new view of humanity, and a more intimate inner world.

Pioneering

Seeking new forms of expression, artists from across Europe became acquainted with one another’s work, travelled to artistic hotspots such as Paris, Berlin and Rome, exchanged ideas, and brought them back home. The results of these cross-border dynamics reveal just how international and multifaceted therediscovery of figuration truly was. With the diversity of their new realisms, these young artists formed the avant-garde of their generation.

A distinctive visual language

A wide array of new realisms also thrived beyond these hubs. In Great Britain, artists such as Meredith Frampton and William Roberts struck a fresh note, balancing photographic precision and social engagement. In Eastern Europe, countries pursued their own paths: Hungarian and Polish artists sought to connect with national traditions, while Latvia developed a ‘post-Expressionist realism’. In newly founded states such as Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, art also served as a means of shaping national identity. In the Netherlands, neorealism became the hallmark of artists including Pyke Koch, Carel Willink and Charley Toorop, who translated international influences into a visual language entirely their own. It is difficult to pinpoint an exact end date for this ‘new realism’. In Germany, a turning point came after 1933, when the Nazis branded such avant-garde art as ‘degenerate’. In the Netherlands and other countries, however, it continued to flourish until artistic production came to a halt with the outbreak of World War II.